A note about tamarisk beetles and a request for your observations

From the Amargosa River Basin in California to the Gila River in southern Arizona, biologists and other community members across the West are reporting new and returning populations of the tamarisk beetle (Diorhabda spp.). If tamarisk beetles have been observed in your area before, you will (or have already!) start to see trees turning brown as they are defoliated by the tamarisk beetle larvae.

Tamarisk beetles mating on tamarisk on the Gila, photo by Dan Wolgast on April 12, 2023.

What is the tamarisk beetle?

The tamarisk beetle is a biological control agent introduced to target invasive tamarisk (Tamarix spp., also known as saltcedar). Biological control, or biocontrol, is an integrated pest management (IPM) method, where a highly specialized natural enemy is introduced to feed on the target invasive species.

Since beetles were introduced by the US Department of Agriculture in 2001, they have been established widely in the western US and provided much-needed control in some areas but have also been the source of management conflicts where native habitat has been lost.

The larvae look like small black caterpillars (pictured above) that do most of the feeding/damage. You will see two to four generations of beetles each summer before they go into diapause (like hibernation) beneath the trees for the winter. The populations ebb and flow with available tamarisk. When they have eaten all of the tamarisk in the area, adults will fly to a new patch or die.

Tamarisk beetles help decrease wildfire intensity

Tamarisk promotes wildfires and is tolerant to wildfire, especially compared to our native riparian species. Due to its structure and biomass, green tamarisk is extremely flammable when it burns and grows back immediately after a fire. Flame lengths of over 130’ have been documented in tamarisk stands. Defoliation by tamarisk beetles ultimately reduces the risk and intensity of wildfires along tamarisk-infested corridors by reducing extremely flammable green tissue.

The brown trees may not be pretty, but defoliation provides opportunities to restore native vegetation alongside our rivers. As tamarisk is defoliated, canopy space opens, allowing other plants access to sunlight and increased productivity if conditions are suitable.

How do tamarisk beetles affect wildlife in tamarisk?

Tamarisk-dominated ecosystems have been found to have lower biodiversity (in terms of studied arthropod, bird, and reptile species) compared to sites dominated by a mix of native and nonnative plants or only native plants, and tamarisk beetles may assist in the long-term recovery and resiliency of riparian communities. However, nontarget effects cannot be disregarded.

To help understand how wildlife is affected by management actions, including biocontrol, RiversEdge West supports research efforts. Last month, contracted ornithologists collected data to determine whether and how migrating endangered southwestern willow flycatchers (SWFL; Empidonax traillii extimus) may be using tamarisk-invaded habitat in Moab, UT. In the photo below, Quinn Jennings and Aaron Songer record audio of a nearby flycatcher. Stay tuned for results to be shared at our Biennial Conference next year!

Where is the tamarisk beetle now?

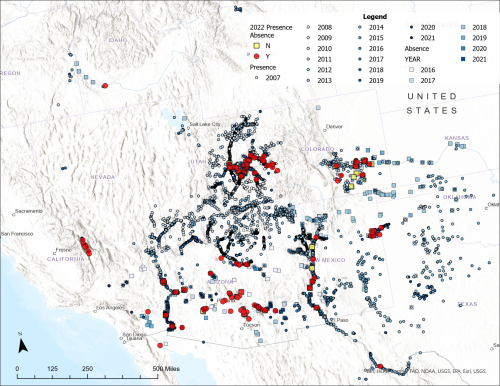

Populations of tamarisk beetles have now established in much of the available habitat throughout the southwestern United States, except for parts of southern Arizona. We have worked with over 70 partners since 2007, with documented observations now ranging from Chihuahua, Mexico to California, and up into Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, and Kansas.

Interact with almost 20 years of tamarisk beetle data here.

In 2022, RiversEdgeWest collected almost 1,000 observations, documenting presence and absence (in the map above: red circles and yellow squares, respectively).

Many populations were reported present where they have been reliably established for many years (historical presence and absence in circles and squares respectively, by year from white to blue), for example, in Grand Junction, CO and Moab.

In some areas along the Rio Grande in New Mexico, some areas are seeing very patchy or absent populations where they existed previously. Partners along the Gila River reported newly established tamarisk beetle populations moving west from eastern Arizona as well as populations moving in from the east.

Through collaboration with Matt Johnson with EcoPlateau and Zeynep Ozsoy’s group at Colorado Mesa University, we have learned that the northern tamarisk beetle (D. carinulata) has made it as far east as the San Pedro River, while the subtropical tamarisk beetle (D. sublineata) made it as far west as Ft. Thomas, Arizona.

As part of our Applied Science program, we are tracking interactions between these species, especially to see whether or how different tamarisk beetle species impact tamarisk differently. This could also mean different impacts on habitat of the endangered SWFL.

You can find more information and research about improving flycatcher habitat, including the SWFL Habitat Viewer, and in our Resource Library.

Please share your tamarisk beetle observations!

We rely on partners and community scientists to help track the beetle and create the 2023 annual map. All observations are welcome!

Please send us your presence or absence observations, with a unique GPS point (latitude and longitude, as precise as possible) and date to tamariskbeetledata@riversedgewest.org. You can use this Excel spreadsheet to help us keep data tidy. We will also accept shapefiles or Google Earth kmz/kml.

Starting in 2023, we will also curate iNaturalist observations under the Tamarisk beetles (biocontrol agents) Project. At the end of the beetle season this year, around November, we will do another call for your 2023 tamarisk beetle observations.

Stay tuned, and happy beetle hunting!